Artist ResidencyCalifornia Coast In Color

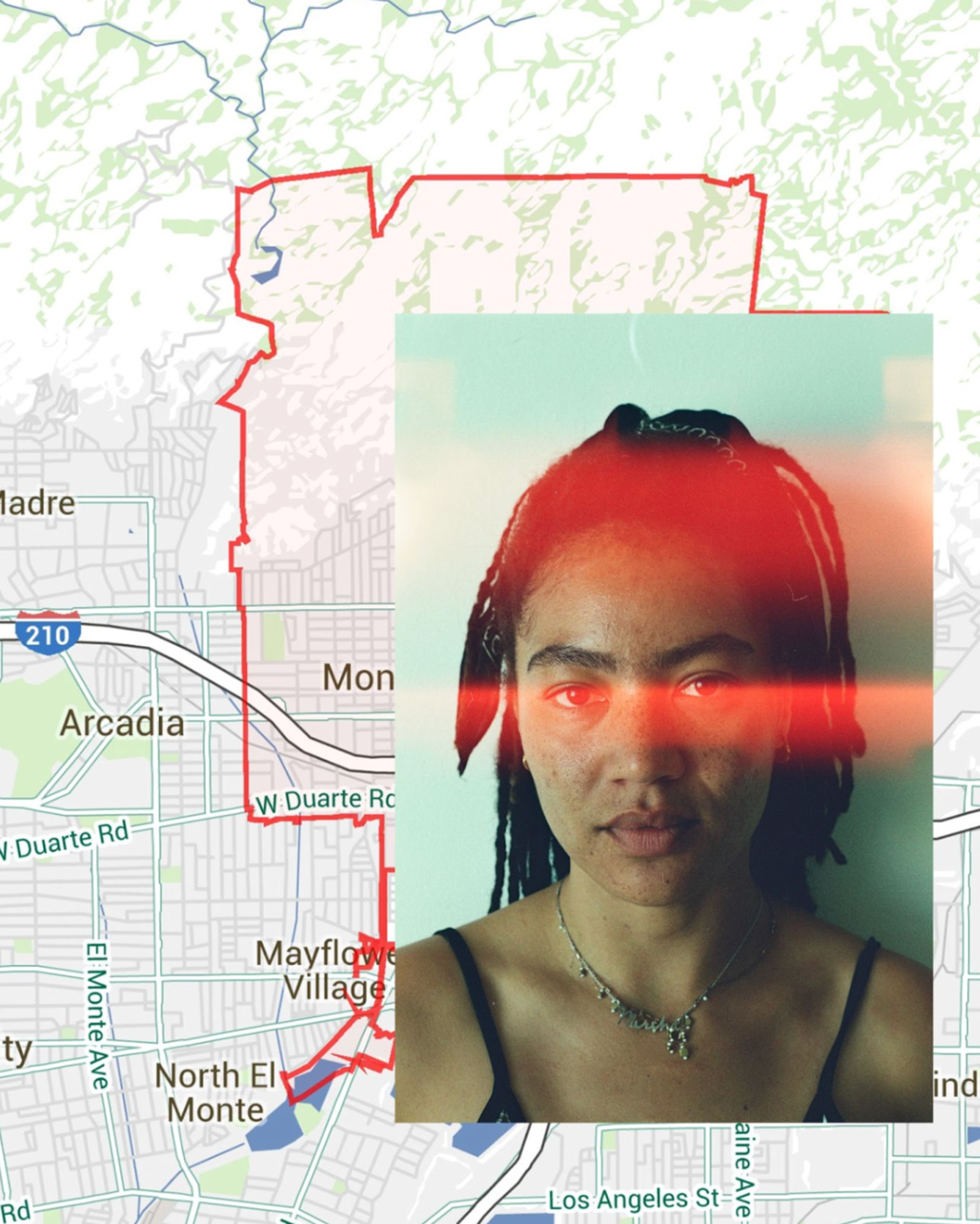

miriha austin

Face It is a portrait series that invites viewers into direct, unflinching encounters with individuals whose lives are intertwined with the fight for environmental justice. Each face is layered over a map of a place that holds meaning in their story — a coastline, a neighborhood, a watershed — sites of impact and resistance. These images are not only portraits; they are geographies of memory, direct and indirect traumas, and resilience.

Each subject represents a unique intersection of person, place, and environmental healing. Together, they make visible the human cost of environmental degradation and the urgent need for justice — reminding us that every face has a body that deserves access to nature, to clean water, to ancestral coastlines, and to the healing power of a healthy community.

This work was seeded during my time in the Black Image Center’s California Coast in Color Artist Residency, where I deepened my understanding of coastal justice movements. I was particularly moved by the Land Back efforts advocating for the return of coastal lands to Indigenous stewardship, and by the youth-led cleanups and grassroots campaigns reclaiming local agency and ecological care. Face It emerges from this lineage — honoring those fighting for environmental and cultural restoration while urging us all to look, really look, at the people behind the policies and pollution

As we look toward the next generation, we (individuals, communities, corporations, lawmakers) must do our part to protect, educate and create access to nature. I urge everyone to start small, and start the kids young! Organizations like Kids Ocean Day provide the youth with a fun, hands on opportunity to experience the beach, learn about their local pollution and foster a sense of personal responsibly while enjoying the wonders of the ocean and sand.

Zee Zetino

Birds, Bonding, and Belonging in the California Coast

Growing up in South Central LA, I saw more airplanes flying over than birds. While I was too familiar with the local crows and abundant house sparrows, I had yet to notice the plethora of diverse birds that existed in the Los Angeles basin. In 2020, the early years of the pandemic, I joined a virtual Wild LA book club where I first met Day Scott—a disabled Black woman and wildlife photographer and ornithologist. That was my introduction to this career pathway. From that moment forward, I purchased my first pair of binoculars and started my birding journey, which eventually led me to a career shift from organizing. I became a coordinator with a local environmental organization which provided me the opportunity to lead many outdoor programs, including birding workshops for community members.

While I enjoyed taking various communities to coastal areas and educating them about the Southern California ecology such as birds, lizards, plants and more, I noticed the low participation, and sometimes stark absence, of Black folks in outdoor activities. This ignited my call to organize a social media fundraiser where I raised $3,000 to purchase binoculars, a scope, and community science tools to increase access, inspire stewardship, and promote safe and healing interactions with nature for Black community. My main focus has been working with the LA Black Worker Center and leading outdoor programs as a means to reimagine wellness practices.

My inspiration for showcasing the famous Double-Crested Cormorants in Humaliwu Lagoon now known as Malibu Lagoon State Beach and the federally endangered California Least Tern on Tongva and Acjachemen territory now known as Bolsa Chica Ecological Reserve is to highlight the importance of coastal bird conservation. I chose the Double-Crested Cormorant because in many instances this bird has fallen victim to anti-blackness via negative remarks and attitudes due to its black plumage. I also chose the California Least Tern as it is listed as a federally endangered bird, threatened by the anthropogenic climate crisis ranging from the encroaching to fragmentation of their habitat. I seek to highlight the experiences and stories of these two birds, in order to call attention to the interconnectedness between our environment and the Black and African diaspora; and to build solutions towards a liberated world.

Through my work I am focusing on two main points:

1. Black worker justice is environmental justice.

2. Increasing bird education and conservation access to the Black community cultivates joy, healing, and career opportunities.

Studying Nature and Rooted in Ancestral Truths

As an AfroIndigenous Transqueer environmental educator who does wildlife and landscape photography, I reclaim memory through my photography as ways to document and preserve my passion, commitments, and narratives—something that is rare to find in writing and visuals from ancestors who shared my identities due to colonial violence and erasure of memory. In addition, I am contributing to bird conservation efforts along the California coast while also taking Black workers and their families to coastal areas, so they can reconnect and recall their ancestral connections to bodies of water.

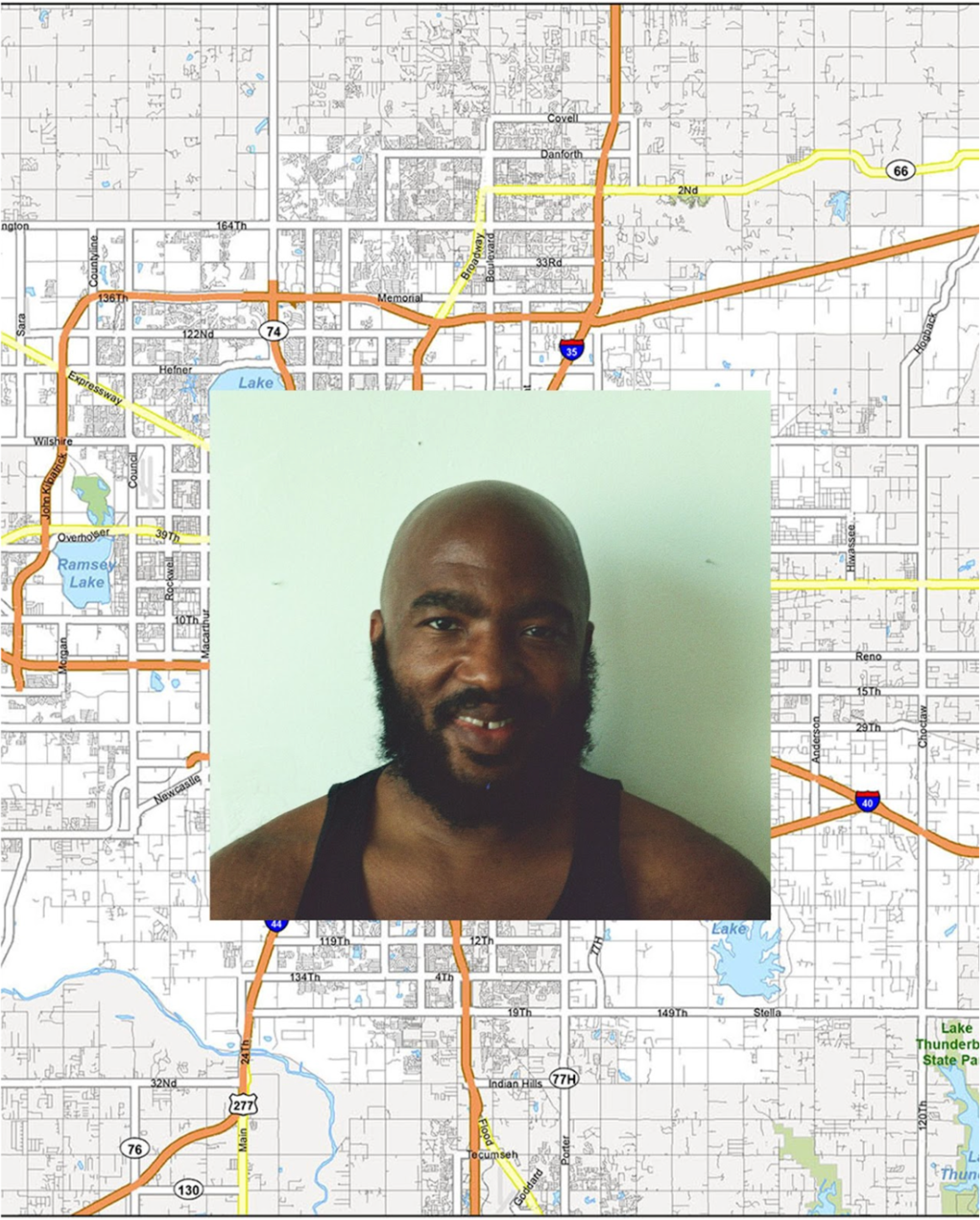

Fred Brashear Jr

The Dream of Paradise

As a Black, photo-based artist, my California Coast in Color campaign, developed through the Black Image Center’s Residency programming, explores the ocean’s dual role as a site and symbol of longing, erasure, and layered histories.

Los Angeles is often portrayed as a sun-soaked paradise, characterized by palm trees, golden beaches, and the alluring promise of the American Dream. Historically, however, this dream was not accessible to all; for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities, it often meant denial of access, belonging, and land ownership.

My work challenges the myth of Los Angeles as a shared utopia, weaving together image and memory to surface historically excluded stories. While California’s beaches are legally public under the California Coastal Act, access has long been restricted for communities of color through redlining, racial covenants, and targeted policing. The story of Willa and Charles Bruce, whose Black-owned seaside resort in Manhattan Beach was seized under eminent domain in the 1920s, exemplifies the systemic erasure of Black coastal presence.

Equally significant is the beach adjacent to the Pico-Kenter storm drain in Santa Monica, once derogatorily known as “The Inkwell.” This site served as a rare sanctuary for Black Angelenos during segregation, where community members gathered, swam, and asserted their right to enjoy the ocean despite persistent racism and environmental harm. Today, the Pico-Kenter storm drain is one of the most notorious sources of pollution in Santa Monica Bay, underscoring ongoing environmental and ecological injustices faced by marginalized communities.

In reclaiming the myth of paradise, I aim to honor those the land has served and acknowledge those it has tried to forget. Rooted in memory, these images become sites of resistance and renewal, calling for stewardship, visibility, and belonging along California’s ever-contested coastal edge.

Community members can support the California Coastal Commission by participating in public hearings, advocating for inclusive development policies, submitting comments on coastal projects, volunteering for beach cleanups, supporting legislation that protects coastal ecosystems, and engaging in local land use decisions that uphold environmental justice. To learn more or get involved, contact (800) COAST-4U or visit www.coastforyou.org. These actions help ensure that California’s coast remains accessible, healthy, and equitable for future generations.

Vernon King

Throughout this entire residency, the word that has crossed my heart and mind the most is “migration”. Blackness historically has had to be mobile to survive. For example, cultural entities such as the Black church have needed to maintain mobility to survive threats of physical violence. While studying in preparation for making this image, I discovered that black leisure also needed to remain mobile along the western coast to survive. From being attacked with bleach in pools to being physically assaulted in the water, black people historically have been forced to have fun where they can, and not where they want to, along the California coast. In the same vein, Inkwell Beach, a historically black beach in Santa Monica, was also mobile as needed. Due to causes such as White beach clubs opening near or harassment from white beach protection groups, the Inkwell beach became not a concrete section of the beach, but solely a place along the beach where black people were safe to recreate.

The work you see here today aims to reflect this migrational aspect of black leisure. Here are three different images of pools, isolated in a backyard. These pools represent leisure, and their positioning reflects the migrational relationship that black people have had with leisure, one that is constantly in flux and often involves isolation.

When we ask ourselves what we can do now to continue advocating for black leisure, one organization that this residency has made me aware of is the Ebony Beach Club. The Ebony Beach Club is an organization that not only prioritizes the preservation of black leisure but also empowers black folks to gain more comfort in the ocean by providing surf classes. My goal in creating this work was that I would not only gain more education and insight into how to further my relationship with the California coast, but also for the work to be a vessel for the audience to further their relationship with the coast. I ask that we always give thanks for the mobility of those who came before us and allowed us the ability to experience leisure together today in a much safer space.

Schessa Garbutt

The shoreline is a sacred space, and coastal access is a human right. Humans have always been drawn to the Ocean as a source of food, transportation, ceremony, and inspiration. This series is a meditation on the liminality of the shore as a site for rituals (art-making), contemplation, play, and grief. Born and raised in Los Angeles, I have always have a deep connection with the Pacific. The cyanotype sun prints serve as site-specific documents for the shore of Cabrillo Beach— kelp and plastic and self portrait included. The digital photograph in this series forced perspective dramatizes the transition of the terraced coast to the sea, reminding us that our planet is shared by two worlds which are always in communication and reciprocity with one another. When I remember that the Ocean has always been a sacred space to humans, I am reminded of my/our role as “stewards of the Earth.”

When I look out over the great blue expanse that covers 71% of our planet, I can help but acknowledge the parallels with my own body, since human brains and hearts are 73% water. And when Joanna Macy, Buddhist eco-philosopher and author, called the Earth “our larger self, our greater body” in a 2018 interview, I could not unsee the truth in her grounding prayer. She reminds me that “there’s nothing that can happen that will ever separate me from the living body of Earth.”

The truth is that the Anthropocene (the age in which humans and our activity substantially impact the planet) may have already been subsumed by the Plastocene, the age of Plastic. Microplastics have been found at the bottom of the Marianna Trench and the top of Chomolungma (Mount Everest). A sedimentary layer of microplastics was found in a dried riverbed in Spain, and the current estimation for the size of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is 1.6 million square kilometers (Texas twice-over). They have been found in human reproductive organs and inside of the blood-brain barrier.

The ocean is the womb of the world. All life springs from the Ocean. She is your ancestor and mine. The sacred, swirling spiral around me reminds me of that womb. Am I sleeping? Running? Dancing? Cyanotype sun printing requires a balance of staging and improvisation. As soon as the pigment’s non-toxic iron salts are touched by sunlight, they begin to turn a deep sea blue. I made this print on-site at Cabrillo Beach, across from the Port of Long Beach. I am surrounded by kelps [Macrocystis pyrifera & others] pulled from the surf as well as inorganic trash collected from the shore. Can you spot all [#] objects? My plastic glove, a bouquet, a balloon, a soda can, a bottle cap, a plastic knife, an octagonal tin, a shovel, a straw, mascara, fishnet stockings, a toy fan, hand sanitizer, a chunk of burnt wood, and others. We all baked in the sun for 15 minutes and then I washed the print in the Ocean to set it. Afterward, the biodegradable materials were returned to the beach and the trash was properly disposed of. I chose this medium because cyanotype is one of the earliest forms of photography. The first photobook ever published was Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843), an ecological survey by botanist Anna Atkins.

When I come to the Ocean, the Ocean brings me to my grief. The eco-spritual is about being with what is here, in all its sanctity and sorrow. This acceptance is not only made of despair. We hold it all because we are connected to it all. We act because we love ourselves and our greater body.

Act now to keep our Oceans sacred. Pick up litter where you see it. All drains lead to the Ocean. Sign up to join a beach clean up with Heal the Bay by visiting healthebay.org/beach-cleanups

Nasir Grissom

Prior to the 1950s, Santa Monica was home to a thriving and sizable black community within the Belmar neighborhood and on Broadway between 14th and 20th street. Through eminent domain more than 500 families were displaced to build the Santa Monica Civic Center and I-10 freeway. In Held Within My Own Arms Nasir Grissom re-establishes the black community archive within the Santa Monica coastline. Like a beacon, Grissom’s photograph pulls you in and haunts. The circular form investigates the ability for the image to be a navigational object. By layering archival photos of the community in their everyday surroundings within the Pacific Ocean, this piece hones in on the permeable barrier between life, death, and memory along U.S. waterways. Here, Grissom evokes Tina Campt’s idea of “Haptic photos.” In its title, the work invites the viewer to the ocean as an altar space, a space for care, and response to environmental weathering.

Access to clean water, air, and agriculture is a universal right. To help protect the ocean and improve the health of communities in South L.A. disproportionately affected by toxic oil drilling tell L.A. city to phase out oil by signing this petition.

The photos gathered for this project are in partnership with the Quinn Research Center, whose mission is to uncover the Black history of Santa Monica. Learn more about their mission here.

Stay Connected to Nasir Grissom’s work: @nasirgrissom

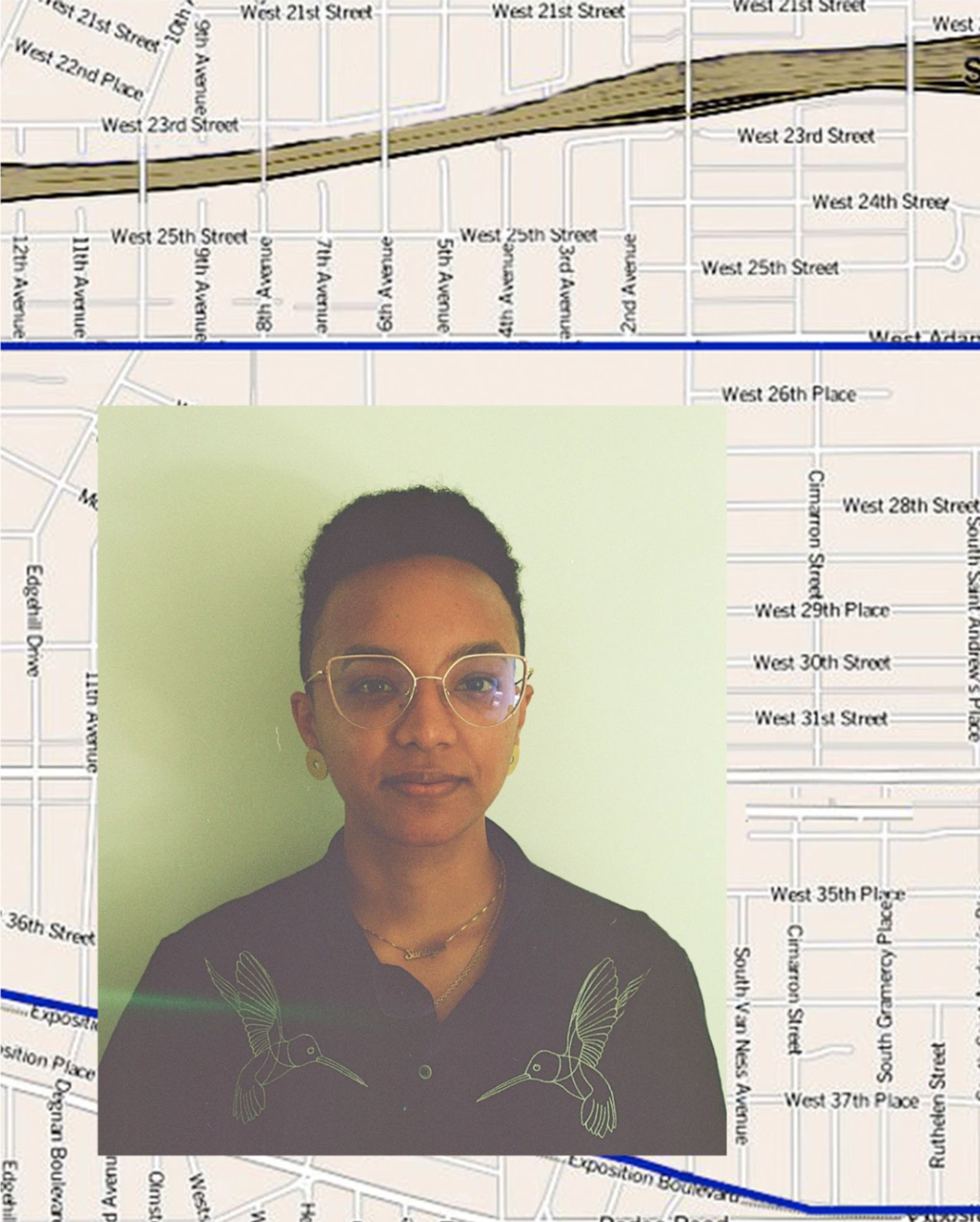

Mercedes Washington

“If you want to know the end, look at the beginning.”

African Proverb

In the beginning, Africans were revered for their knowledge of medicine, mathematics, exploration, hunting, gathering, and swimming. In “They Came Before Columbus”, Ivan Van Sertima documents the expert navigation skills of Africans transversing continents long before chattel slavery. From diving for pearls to assisting with rescue missions, their oceanic prowess allowed them to find joy, generate income, and enjoy their connection with the Aquatic. Therefore, it is troubling that when we speak of our people's connection with the ocean and sea, it is hyper-focused on the Transatlantic slave trade.

Liberation is not without costs. As a collective, we are teetering on the historical precipice of war and peace, love and hate, destruction and birth, fact and fiction. The fact is there are no private beaches in California. The California Coastal Commission is committed to protecting California’s coast and ocean for present and future generations. No one can bar us from taking advantage of the beautiful offerings of Mother Nature. I envision a future where this policy is common knowledge and we see even more of us paddle boarding, surfing, scuba diving, hiking, swimming, and sunbathing. As we reclaim these sacred spaces, we must also be good stewards and safeguard our environmental treasures. I commend organizations like @hikeclerb, @swimkids, and @we_are_justice_outside for cultivating spaces and creating opportunities that demonstrate our deep love and commitment to the Earth and our desire to be in community with one another.

I am inspired to tell the story of a freedom loving, multifaceted, intuitive, and environmentally rooted people. My campaign invites the audience to consider what awaits them beyond the horizon. My great-great-grandmother swam the Mississippi River with two children on her back to prevent them from being sold on an auction block. Maybe she looked to the North Star for guidance to a New World beyond what she knew was certain destruction and separation? Her determination and courage could not be contained. What actions are you willing to take to protect your freedom, resist oppression, and sustain your legacy?

William Rouse

I’ve always felt a deep connection to the ocean, yet it often seemed inaccessible. Visiting Southern California beaches, I would experience imposter syndrome—feeling like a guest rather than a member of this vast, living environment. Why did I feel this way? As a child, I dreamed of surfing, studying dolphins, or being in the presence of a surfacing blue whale — but I never believed I could truly belong. That changed when I began to understand my relationship with God. I realized I am a spiritual being, and so is everything on this planet. The ocean, in this light, is not merely a body of water but a living, spiritual entity that exists in harmony with us—a vital, conscious presence.

Building on this understanding, I am reminded of the immense ecological significance of California’s kelp forests, which lie just off the coast. When healthy, these forests absorb more carbon than the greatest land-based rainforests and could play a crucial role in mitigating climate change—if we take responsibility for their care. Unfortunately, this same region is also home to one of the worst ecological disasters in the country: the DDT dumping near Catalina Island and Palos Verdes. Furthermore, Southern California’s sewer systems and widespread pollution—trash, oil, and chemicals—ultimately find their way into our oceans, harming marine life and ecosystems at an alarming rate.

This interconnectedness of water and life deepens my understanding of water as a great unifier—a bridge that connects our world. Every continent is linked by water, and all living beings depend on it. Our bodies are composed of approximately 70% water, and nearly 70% of the planet’s surface is covered by the ocean. Clearly, everything is intertwined.

Throughout this residency, I’ve reflected on what I want to communicate. As a child, I longed for access to the ocean and a sense of belonging. Now, I see how pollution and environmental destruction threaten our planet at an unprecedented scale. But this raises a crucial question: what about the millions of people who feel no connection to the ocean? How can I inspire them to care?

What I do know is that we are all spiritual beings, inherently linked to the ocean and its energies. For centuries, many cultures have spoken of water spirits and powerful, living forces—sacred entities that embody the soul of water itself. This piece, “Living Waters,” seeks to embody that spiritual connection—recognizing the ocean as a sentient, sacred being that sustains and unifies us all. And, if disrespected or ignored, the ocean’s fury can hasten our path toward self-destruction, urging us to respect and protect this vital force.

Fortunately, many groups and organizations are working diligently to foster greater connection and stewardship. Schools and clubs like Sofly Surf School, Intrsxtn Surf, Pacific Town Club, and Ebony Beach Club are paving the way for increased accessibility and inclusivity. Meanwhile, advocacy organizations such as Heal the Bay and The Bay Foundation are playing essential roles in restoring and safeguarding our oceans."

Kiera Thomas

Black Histories, Coastal Futures

This body of work is born from my own journey of returning to the ocean. I began surfing in 2022, and the moment I stood up on a wave, my life changed. The ocean became more than a place of recreation, it became a teacher, a healer, a spiritual anchor. Surfing transformed how I connect with nature, deepened my reverence for the earth, and introduced me to a powerful community of Black and Brown people who also find joy, purpose, and belonging in the water.

Black Histories, Coastal Futures tells the story of reclamation. It is a tribute to Nick Gabaldón, California’s first documented Black surfer, and a celebration of his enduring legacy. At a time when Black people were systematically excluded from coastal spaces through segregation and violence, Gabaldón paddled 12 miles from Santa Monica to Malibu to surf. Today, his courage waves through a new generation of surfers, myself included, who are reclaiming the coastline as a site of joy, resistance, and belonging.

This work was created in connection with Nick Gabaldón Day, an annual event hosted by the Black Surfers Collective to honor his life and legacy. The event brings together Black surfers, families, and community members for surf lessons, environmental education, and storytelling that reconnects us to the water and each other.

Through images of community, remembrance, and deep connection to the sea, this work challenges the false narrative that Black people don’t swim, don’t surf, or don’t belong at the beach. We’ve always been here—and we continue to rise with the tide. This campaign is both a visual offering to my community and a reclaiming of the coastline as a site of healing, history, and belonging. It is a response to the long legacy of exclusion along the California coast, and a reimagining of what it means for Black people to take up space, joyfully and unapologetically. My work seeks to rewrite that narrative, through presence, through joy, through waves.

Call to Action:

To every Black and Brown child who’s never or always envisioned themselves on a surfboard. To every family who’s never felt safe at the shore. To every person of color who’s been told these spaces weren’t for them. Play in the ocean. Try surfing. Reclaim what has always been yours.

Join organizations like Black Surfers Collective—who’ve been doing the work of diversifying the coast for the past 15 years. Show up for their community events, volunteer, and donate to sustain their powerful mission.

Visit their website: www.blacksurferscollective.org

We are the waves. And we are shaping coastal futures.

To see more of my work check out my instagram @kiera.s.t

Eddie Hemphill

"Black In the Blue: Marine Scientists and Advocates in Focus

A Photography and Storytelling Project by Eddie Hemphill

This project was born out of a desire to see more of us reflected in the places that we already are -- in care for, in stewardship of, and in fellowship with the ocean. I’ve always been drawn to water. As someone who found healing and grounding in the Pacific while living and organizing for land sovereignty and sustainability in Hawaiʻi, I know how the ocean can hold us. It is a constant provider of perspective, reminding us of just how small we are, but also how deeply connected we remain.

I also know that the narratives we absorb about who belongs near the water, who protects it, who studies it, who makes decisions about its future are far too narrow. Black In the Blue is my response to that erasure. This body of work centers Black marine scientists and other ocean advocates in the spaces they’ve long occupied but rarely been celebrated in. The project will also feature elements of the environment that these scientists steward as well as portraits of Black families dedicated to communing with the ocean.

Through portraiture and interviews, this campaign tells a fuller story of who protects our oceans -- not just as researchers, but as artists, caregivers, coastal dwellers, community leaders, and visionaries.

The timing is urgent: proposed federal cuts would slash NOAA’s budget by over 25%, gutting critical environmental research programs that allow us to track our changing climate and the impacts that disproportionately affect people of color. These cuts eliminate the very pipelines that support scientists from historically excluded communities preventing them from becoming advocates for the most disenfranchised.

So when I pick up my camera for this project, it’s not just about visibility. It’s about resistance. It is about saying: we are here and we always have been. It is about making it undeniable that Black scientists are central to the future of marine conservation and that Black people deserve access to our oceans.

This work speaks to a long lineage of environmental justice, coastal organizing, and community-rooted science. I see it in the Movement for Black Lives’ intersectional climate demands. In the memory of people like Harriet Tubman, who used waterways to lead others to freedom. In the work of contemporary organizations like Black in Marine Science (BIMS), who are building global community for Black ocean scientists.

By making this an ongoing project and showcasing these portraits along the coast and in community spaces, I hope to reclaim narrative, memory, and belonging. I want viewers to pause and ask: Who do I picture when I think of a scientist? Who do I imagine has the authority to speak for the ocean? And how can we ensure those closest to climate harm are centered in climate solutions?

The call to action is simple, but essential:

Sign the petition to protect NOAA funding

Support Black in Marine Science

Share these stories. Amplify the visibility of Black marine scientists doing the work every day.

Ultimately, Black In the Blue is a love letter to those who protect what protects us. It’s a visual archive, a cultural offering, and a refusal to disappear. Through this project, I want to remind us that we come from these waters and we belong to them.

Check out more on the project:

Black in the Blue Website

Instagram - @projectblackintheblue